Swatantryaveer Vinayak Damodar Savarkar has been one of the most misunderstood and controversial names in Indian independence struggle history. Born in 1883 at Bhagur, Maharashtra, Savarkar was a revolutionary, poet, political philosopher, and staunch nationalist who endured over a decade of hard imprisonment in the Andaman Cellular Jail, commonly known as “Kala Pani”, in inhuman conditions that broke the spirits of many.

Savarkar’s legacy is a topic of discussion even today. However, in the last several decades, a narrative has been constructed that while incarcerated at Kala Pani, he wrote a series of alleged mercy petitions to the British. The apology letters allegedly written by him, in which he pleaded for mercy, are still a matter of debate among historians, politicians, and the public at large.

As we remember Savarkar today on his birth anniversary, this article seeks to examine the background of Savarkar’s letters, their reasons, and historical context.

On the evening of 21 December 1909, a Marathi play titled Sharada was staged at the Vijayanand Theatre in Nashik, Maharashtra. This play was performed as a farewell tribute to Arthur Mason Tippetts Jackson (A.M.T. Jackson), the Collector of Nashik. During the performance, Anant Laxman Kanhere fired four bullets at Collector Jackson, killing him. Along with Anant, Krishnaji Gopal Karve and Vinayak Narayan Deshpande were also present. All three were arrested in connection with the assassination and were hanged on April 19, 1910. The British police alleged that the assailants were affiliated with a revolutionary organization named Abhinav Bharat, and held the group responsible for Jackson’s murder. The Abhinav Bharat Society had been founded by Vinayak Damodar Savarkar and his brother Ganesh Savarkar. At the time of Jackson’s assassination during the play, Savarkar was in London. His elder brother Ganesh was arrested in India, following which Savarkar himself was apprehended by the British police in London and subsequently brought back to India.What was stated by the court in its ruling?

Vinayak Damodar Savarkar and his brother Ganesh Savarkar were prosecuted for treason for abetting to murder Nasik Collector A.M.T. Jackson and inciting armed rebellion against the British government. While handing down the sentence, the court said in its order on February 3 1911 that an organization called ‘Mitra Mela’ was working under the leadership of Ganesh Savarkar and Vinayak Savarkar. Later it came to be known as ‘Abhinav Bharat’. The principal objective of this organization was to unshackle India from the chains of colonialism. The meetings of this organization used to have passionate speeches of patriots, which were given by Savarkar and other persons. Before Savarkar left for England, a function was organized in his honor in Nasik, in which he gave a speech saying that the main purpose of going abroad is to repay the debt of India’s independence. He showed a picture of Lord Hanuman holding a mace and a white demon crushed under his foot (symbolically pointing towards the British). In England, Savarkar stayed at ‘India House’ from 1907 to 1909, which became an important center for Indian revolutionaries. He motivated those assembled to commence physical conditioning and military practice.

The court stated in its ruling that in early 1909, Savarkar sent a parcel of twenty Browning pistols from London to Mumbai. One of the same pistols, which Savarkar had sent from London, was used in the murder of Mr. Jackson of Nasik. Even before this, Khudiram Bose and Prafulla Chaki had attempted to commit a murder in Muzaffarpur. Revolutionary activities under the leadership of Savarkar were organized first in India and later in England. He sent weapons to India, published books on making bombs and made ‘India House’ the center of revolutionaries to organize the Indian freedom struggle. Savarkar’s passionate speeches inspired his followers to violent revolution. The British court sentenced Savarkar to two life imprisonments and confiscation of property on 30 January 1911. There were two sentences of 25 years each, These sentences were not meant to run concurrently, that is, the British sentenced 28-year-old Savarkar to 50 years of imprisonment.

Source: The British government used to document all the activities of the freedom fighters during its rule. ‘History of the Freedom Movement in India’ is one such government historical document, which was published under Bombay Government Records. The court order regarding Savarkar is present on pages 456-463.

Vinayak Savarkar’s petitions

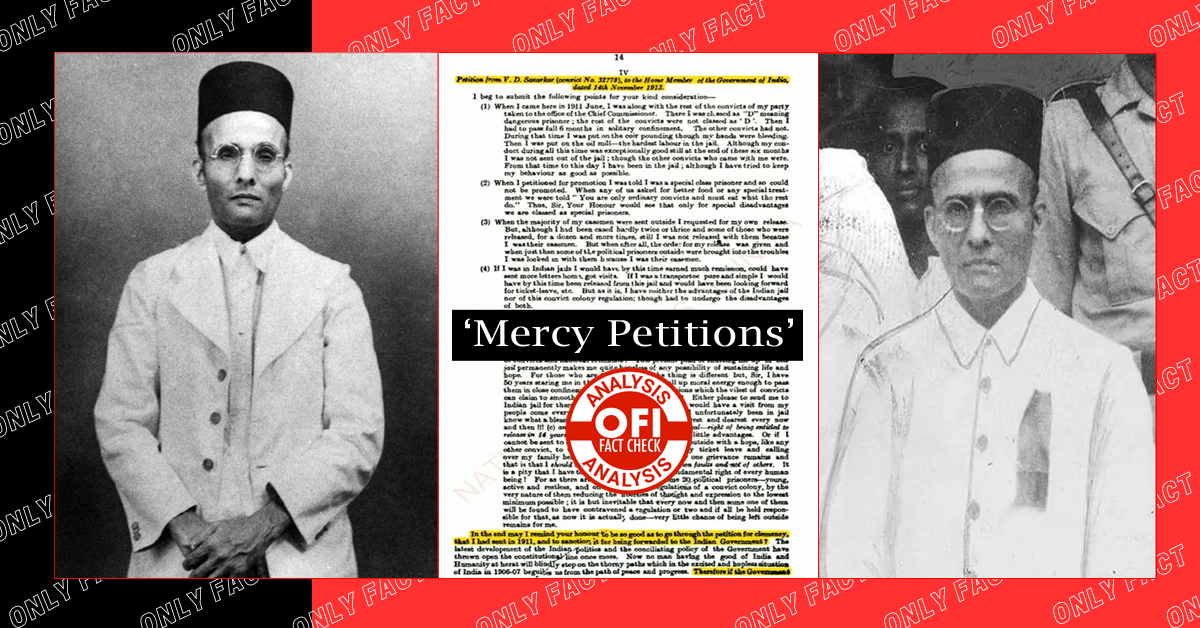

After the final court verdict, Savarkar was sent to the Cellular Jail in the Andaman Islands. As Savarkar had been sentenced to two life imprisonments, he was supposed to serve 50 years in jail, which meant he would have been released only in December 1960 from the Andaman prison. It is often claimed that Savarkar, terrified by the brutal treatment of prisoners in Kala Pani, filed mercy petitions to the British to escape the inhuman conditions, and that he was released only after offering an apology. Vinayak Damodar Savarkar filed his first petition in 1911, shortly after he was brought to the Cellular Jail. After that, he filed petitions in 1913, 1914, 1917, and a final one in 1920.

Vinayak Damodar Savarkar’s 1911 petition: Vinayak Damodar Savarkar submitted his initial petition in the Cellular Court of Andaman in 1911. Although Savarkar’s 2011 petition is not available, in a petition dated 14 November 1913, Savarkar cited his previous petition suggesting that this was his second petition.

1913 petition: In October 1913, Reginald Henry Craddock, Home Member of the Government of India, visited the Cellular Jail. During this time, he met many revolutionaries, including Vinayak Savarkar. Savarkar submitted a petition dated 14 November 1913 to Reginald Henry Craddock. In this petition, Savarkar demanded permission to leave the prison like other prisoners and to correspond with and meet his family members.

Petition filed in 1914: The First World War began in July 1914. This war was fought between (France, Russia, Great Britain, Italy and the United States) and (Germany, Austria-Hungary and the Turkish Empire). Since India was a part of the British Empire at that time, Indian soldiers were also enlisted in this conflict.

During this period, Vinayak Savarkar sent a petition to the Chief Commissioner of the Andaman Islands in October 1914. In his petition, Savarkar wrote:

“I offer to serve voluntarily in the ongoing war in any capacity, as the Indian Government may deem fit. I know that the empire’s survival does not depend on the help of an ordinary person like me, but I believe that no matter how ordinary, everyone is responsible for the protection of the empire by voluntarily giving their best efforts. I also wish to request that there can be no better way to spread and strengthen the feeling of loyalty among the Indian people imprisoned for political crimes than by releasing them. If the government has any doubts that I want to ensure my release, then I would like to say that I should not be released, but others should be released in my place.”

Petition put forward in 1917: As expressed in his petition, Savarkar assured the British government that if he was released, he would remain loyal to the government and would not condone violence. If he was released, he would dedicate efforts to social reform, education, and progressive work.

He further wrote, “If the government feels that I am writing this to secure my release, or if my name is the main obstacle to granting amnesty, then the government should remove my name and release everyone else; such an initiative would be as satisfying to me as my own release.

If the government ever considers this question, the amnesty should be broad enough to include Indian expatriates and those who have been treated as strangers in their own land and are bitter opponents of the Government of India—most of whom, if allowed to return, would wish to work in the interest of the motherland and pursue constitutional reforms when the new and fundamental Constitution comes into force here.”

Petition of the year 1920: In this petition, Savarkar requested that he and his brother be included under the royal pardon granted by the British government. He stated that Barin Ghosh, Hem Chandra Das, and other accused were absolved notwithstanding more serious allegations. On this basis, he argued, he and his brother should also be pardoned. Savarkar further contended that he had served 10–11 years of rigorous imprisonment, while other convicts were released after a much shorter time. He assured that after his release, he would stay away from politics and would not engage in any activities against the British government.

Savarkar’s Petitions:

- November 1913: Can be accessed in the National Archives on page 14.

- October 1914: Also available in the National Archives.

- 30 March 1920: Found in History of the Freedom Movement in India, pages 472–476.

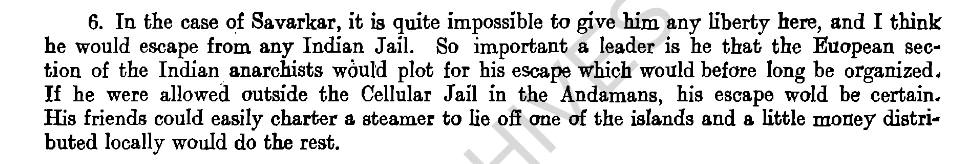

Vinayak Savarkar filed petitions one after the other. He even said that he would support the British government in the war and offer his services. However, it is also important to know why Vinayak Savarkar filed petitions one after the other and what the British government thought about those petitions and Savarkar.Official response to Savarkar’s 1913 appeal: In response to Vinayak Savarkar’s petition, Craddock wrote a report on his way back to India, stating that Savarkar “cannot be said to have any remorse or regret” for his actions. Craddock further noted that, in Savarkar’s case, it was absolutely impossible to grant him any form of liberty, as he believed Savarkar would escape from any prison in India.

He added that Savarkar was such an important leader that the European faction of Indian anarchists would plan and swiftly organize his escape. If he were allowed out of the Cellular Jail in the Andamans, his escape would be inevitable. According to Craddock, Savarkar’s supporters could easily hire a steamer, anchor it near a nearby island, and use a small amount of money distributed locally to facilitate the escape.

Source: Found in the records maintained by the Government of India

Response of the British regime to Savarkar’s 1914 submission: V. D. Savarkar, a prisoner in the Andamans, submitted a petition to the British Government, offering his services and appealing for a general amnesty for all political prisoners in India. However, it was noted that some prisoners might conspire against the Government, steal arms, and distribute anti-national pamphlets.

Seditious agitation in India had not subsided, and the petition was viewed as an attempt to exploit the prevailing circumstances to expand the scope of anarchist activities and attract disruptive elements—possibly in association with Sikh emigrants returning from the Far East, Pan-Islamists, and other disaffected groups. As a result, the Government decided not to consider Savarkar’s petition, and he was informally notified of its rejection.

Source: Digitally available in the Government of India’s archival records.

British Government’s assessment of Vinayak Savarkar and Ganesh Savarkar’s conduct in 1919: Ganesh Savarkar’s conduct remained poor until 1914, and he was often punished, mainly for refusing to work and for possession of prohibited articles. During the last five years, he has exhibited proper conduct; his only fault, considered minor, occurred in November 1917, for which he was reprimanded. His current attitude is one of submission to authority, but he has never shown any inclination to assist in prison work as the three Bengalis have done. He performs the light labor of rope-making assigned to him and spends the rest of his time reading. He is not sociable, and therefore I have no knowledge of whether he has renounced his former political views or not.

Vinayak Damodar Savarkar was punished eight times during 1912, 1913, and 1914 for refusing to work and for possession of prohibited articles. Over the last five years, his conduct has improved. He is always polite and courteous, but like his brother, he has never shown any inclination to actively assist the government. At present, it is impossible to determine his true political views.

Source: Read page 464 of History of the Freedom Movement in India. British Government telegrams can be seen here in the National Archives.

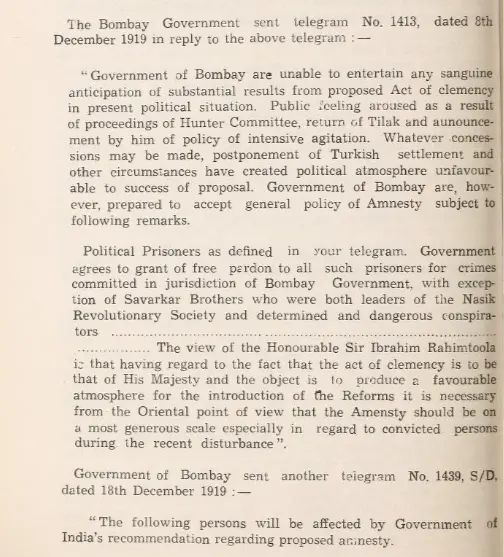

Royal pardon not granted: On 4 June 1919, the Bombay government informed the Superintendent of Port Blair in a telegram that political prisoners would be granted royal pardon but revolutionaries like the Savarkar brothers were excluded from this pardon. After this, the royal amnesty was officially announced on 24 December 1919 but Vinayak Damodar Savarkar and his brother Ganesh Savarkar were not released. It was stated in the telegram that the Savarkar brothers were leaders of the Nasik Revolutionary Society and were dangerous conspirators.

In the Legislative Council of Bombay, D. V. Belvi raised the question of the Savarkar brothers not being pardoned in the royal proclamation.

Source: Page 467-471 of History of the Freedom Movement in India.

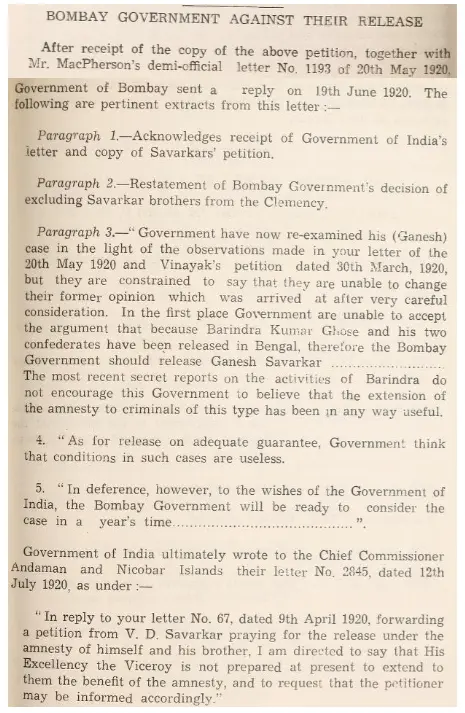

British authorities’ answer to the 1920 petition: Savarkar had sought amnesty for the release of himself and his brother, but the British Government was not willing to grant him this benefit. In its reply, the British Government stated that Barindra Kumar Ghosh and other revolutionaries had been freed, so there was no reason to reconsider the release of Ganesh Savarkar. According to recent reports, Barindra Ghosh’s activities have failed to convince the Government that granting amnesty to such criminals is justified in any way. Regarding release without adequate guarantees, the Government believes that such release would be futile.

The Bombay government, in its reply dated 29 February 1921, stated that it was not in favor of transferring the Savarkar brothers to any jail in the Bombay Presidency, as this could lead to a revival of the movement in their favor.

Source: The British government’s reply to Savarkar’s petition is available on pages 476-477 in ‘History of the Freedom Movement in India’.

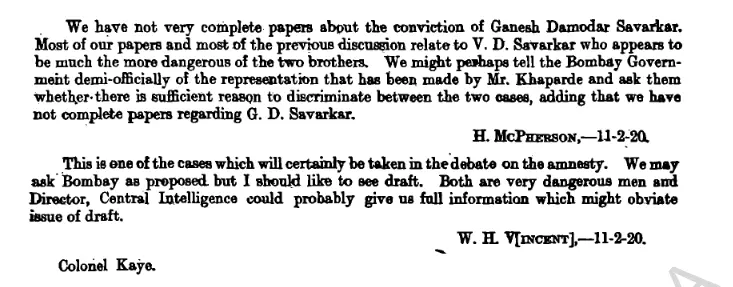

Response of British officials to Savarkar’s petition: Regarding the question of the release of the Savarkar brothers in the Imperial Legislative Council, British officials H. McPherson and W.H. Vincent described the Savarkar brothers as “very dangerous persons.” Vinayak Damodar Savarkar was specifically described as the more dangerous of the two.

Source: National Archives – Access Here

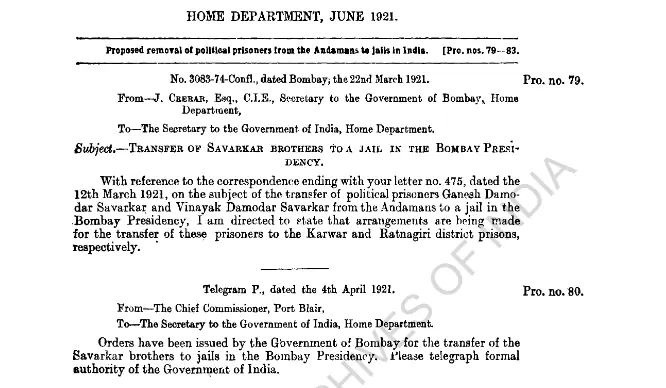

Between 1911 and 1920, Savarkar sent several mercy petitions to the British government. In these petitions, he pleaded for his release and expressed loyalty to British rule. He also stated that he would follow the constitutional path in the future and refrain from violent activities. However, the British government rejected his petitions, considering him "one of the most dangerous persons in India." Many freedom fighters were released from jail under royal pardon, but the Savarkar brothers did not receive this benefit.From Andaman to Bombay Presidency prison: Despite several pleas by Savarkar, the British government did not fully grant his requests, but in March 1921, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar and his brother Ganesh Damodar Savarkar were transferred to Yerwada Central Jail in the Bombay Presidency.

Source: Access the Home Department records of the British Government here

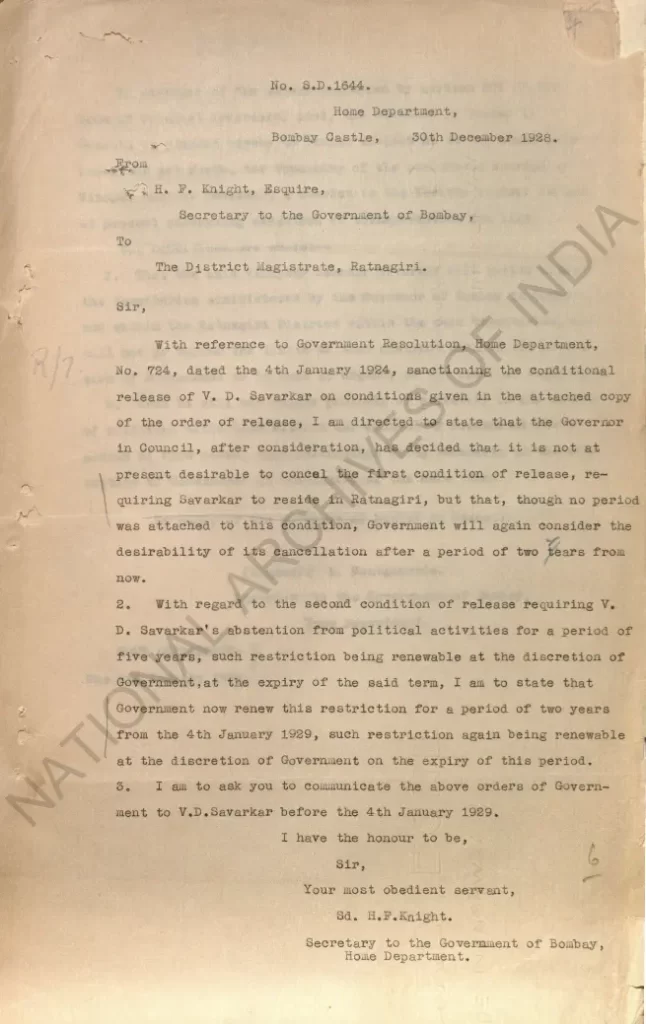

Savarkar was released on conditions in 1924: Vinayak Savarkar was released on conditions from Yerawada Central Jail in the Bombay Presidency on 4 January 1924. The British government granted him this release with certain conditions. Under these conditions, Savarkar was instructed not to leave the boundaries of Ratnagiri district, nor to participate in political activities. If he violated these conditions, he would be sent back to jail. These restrictions were to remain in effect for the next five years.

Source: British Government Home Department records are available here

The ban continued in 1929: After being released from the Bombay Presidency jail, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar was interned in Ratnagiri with certain restrictions for five years. However, even after this period, the British government did not lift the ban. On December 30, 1929, the Secretary of the Bombay Government wrote a letter to the District Magistrate of Ratnagiri, informing him that the government was extending the ban for another two years. Savarkar was to be informed of this extension before January 4, 1930.

(Access the letter from the Secretary of the Bombay Government in the National Archives here)

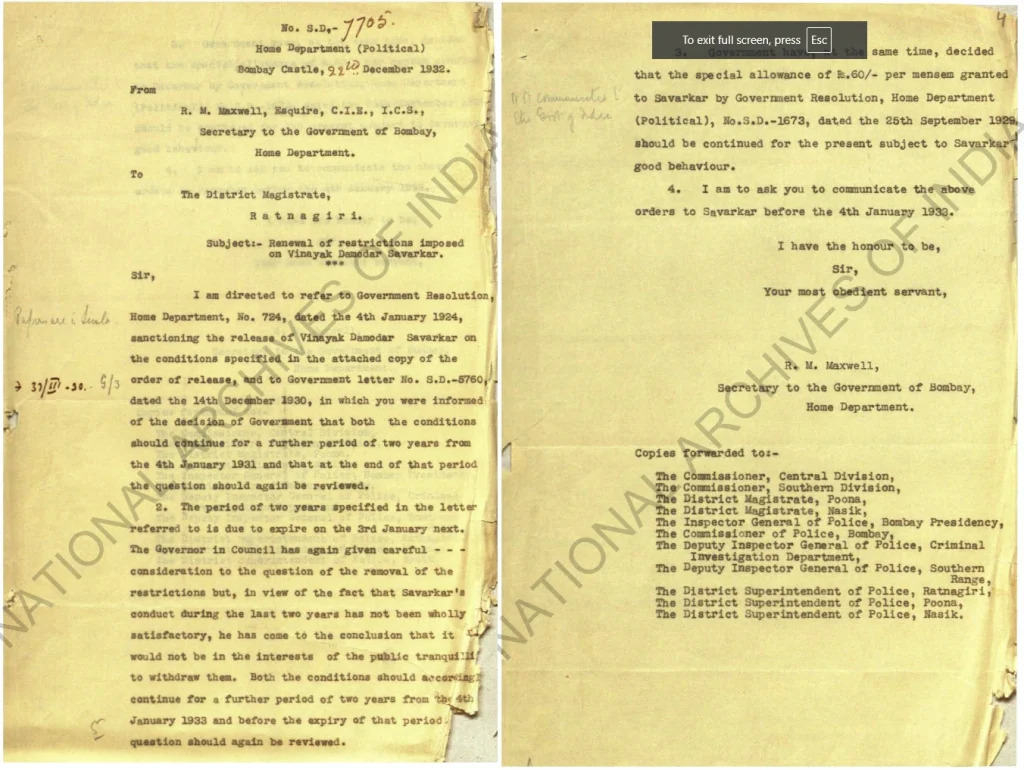

Ban not lifted in 1932: Vinayak Damodar Savarkar was released from Yerawada Central Jail in the Bombay Presidency in January 1924 with a five-year ban, but this ban was not lifted after the period ended. In 1929, the British government extended the ban for another two years. Subsequently, on 22 December 1932, the Home Secretary of the Bombay Government wrote a letter to the District Magistrate of Ratnagiri stating that Savarkar’s behavior had not been completely satisfactory over the past two years. The government had concluded that lifting these restrictions would not be in the interest of public peace. Therefore, both conditions were renewed for an additional two years from 4 January 1933.

(Letter from Secretary, Home Department, Government of Bombay is available in the National Archives here)

Savarkar arrested in 1934: R.M. Maxwell, Secretary of the Home Department, Government of Bombay, in his ‘Report of Local Governments and Administration on the Political Situation in India,’ informed the Government of India in May 1934 that Vinayak Damodar Savarkar had been arrested under the Bombay Special (Emergency) Powers Act of 1932, as he was suspected of being linked to the activities of two persons who were recently arrested. Investigations indicated that these two individuals were involved in the attempted murder of Sub-Conductor Sweetnall in England. News reports regarding the attack on Sub-Conductor Sweetnall stated that some letters recovered from Savarkar’s house contained information about revolutionary activities carried out across India. However, no direct evidence has been found so far to prove that he himself committed any crime. Therefore, it was proposed to extend the period of his detention to facilitate further action against him.

(Home Department Secretary’s letter, Government of Bombay, accessed in the National Archives here)

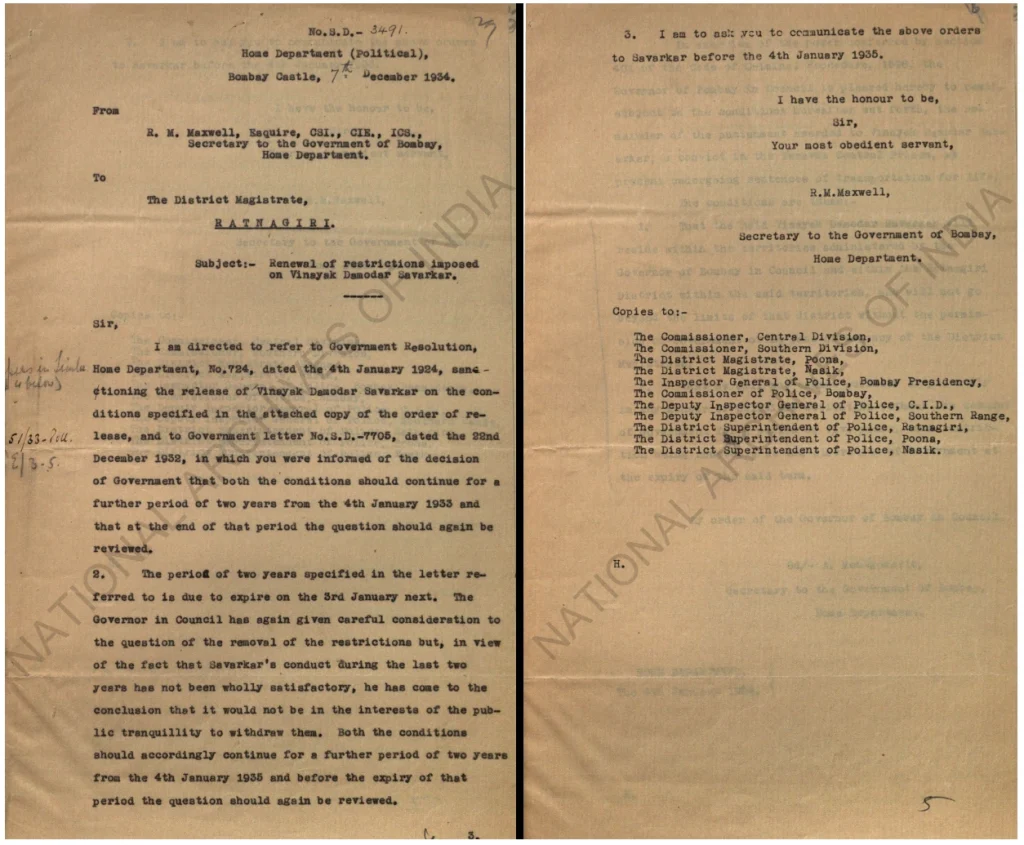

Restrictions prolonged in 1935: The Home Department Secretary of the Bombay Government, R.M. Maxwell, sent another letter to the District Magistrate of Ratnagiri on 7 December 1934, informing him that the restrictions imposed on Vinayak Savarkar during his house arrest in Ratnagiri would not be lifted. The Secretary wrote that the Governor-in-Council had once again given careful consideration to the question of lifting these restrictions, but Savarkar’s conduct over the past two years had not been completely satisfactory. Therefore, lifting the restrictions was deemed not to be in the interest of public peace. It was decided that these conditions should remain in force for another two years from 4 January 1935, and the matter would be reviewed again before the expiry of that period.

Source: Read here in National Records

Upon studying the historical records, the accounts reveal that the British government was consistently averse to the petitions filed by Vinayak Damodar Savarkar. His pleas were repeatedly rejected, and the British authorities never placed their trust in the assurances or arguments on which Savarkar based his appeals. In fact, he was not even granted the privilege of a royal pardon. The British continued to view him as a dangerous revolutionary leader, and there was a persistent fear that he might escape and resume anarchist activities.

In addition, after having filed several petitions from 1911 to 1920, when he was eventually released, his release was not absolute—he remained under surveillance, subject to restrictions, and placed under house arrest. This demonstrates that the colonial government never fully trusted him or assumed he had abandoned his revolutionary activities.

Following his incarceration in the Cellular Jail in the Andamans, Savarkar was transferred to prisons in the Bombay Presidency and subsequently placed under house arrest in Ratnagiri. Even during his time in Ratnagiri, strict restrictions were imposed on him and were periodically extended year after year.

Savarkar’s mercy petitions should not be read merely as isolated apologies. Rather, they must be viewed in the broader context of oppressive colonialism, where survival often demanded calculated choices. Strategy and resistance took various forms. What is often overlooked is that, upon his eventual release, Savarkar was not welcomed into political freedom but was kept under constant watch and strict supervision. For many years, he was barred from participating in public political life and could not travel without official permission. He was systematically kept away from all such platforms.

It is also important to highlight that Savarkar remained intellectually active throughout his imprisonment. He composed numerous patriotic poems on suffering and engaged deeply in political discussions. Furthermore, during his time in the Cellular Jail, he served as an ideological mentor to fellow prisoners—educating young inmates in political science, history, and revolutionary thought. Many of these individuals went on to play significant roles in the Indian freedom movement after their release.

Even behind bars, Savarkar’s leadership remained undiminished. Though unable to participate in the physical revolution due to his incarceration, he continued to contribute to the freedom movement through his ideological, intellectual, and inspirational ideas.